#NotMyGospel: Publishing My Perspective:

On Primary Sources and Public Gods (an interlude)

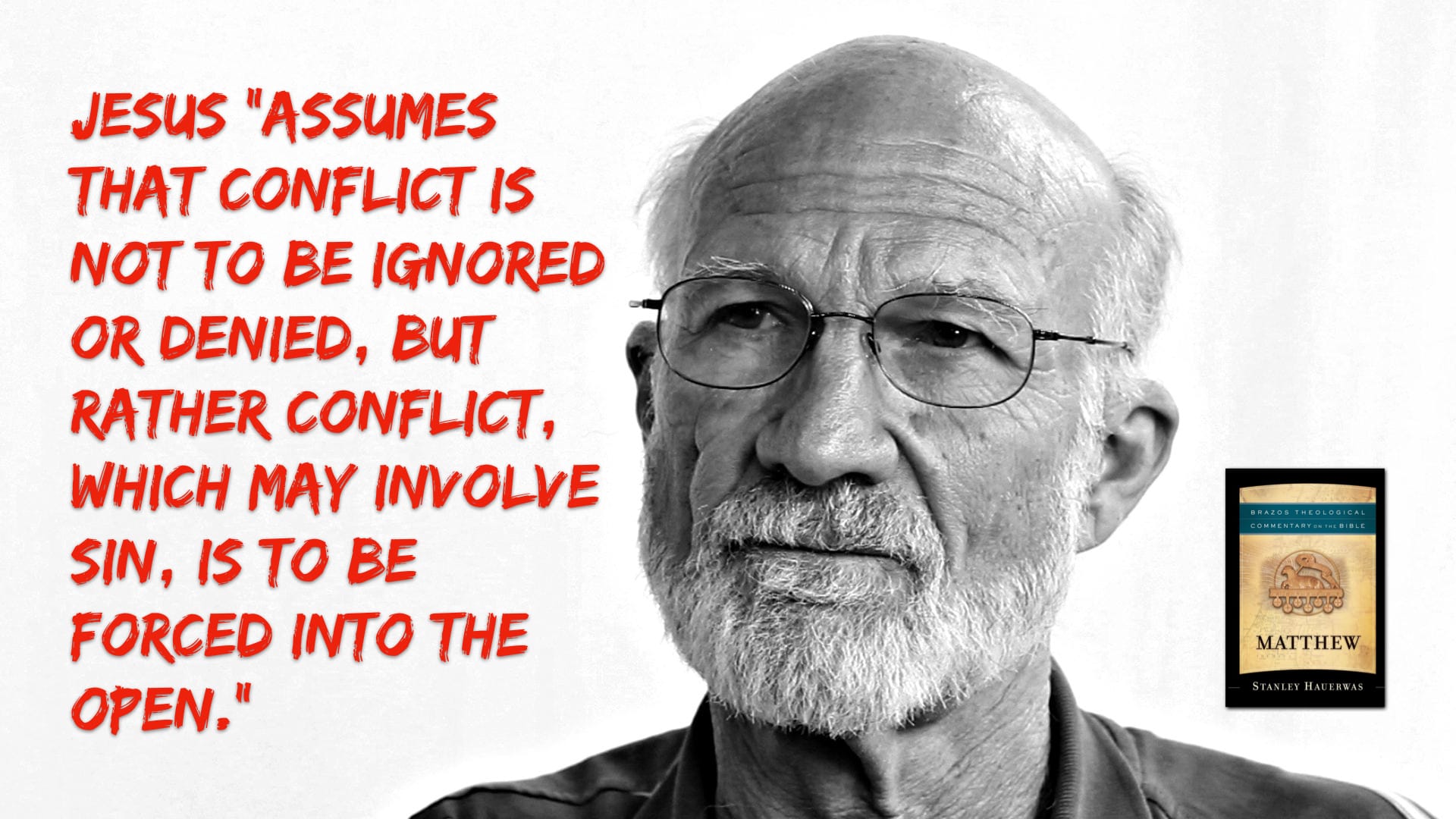

When Jesus outlined conflict resolution in Matthew 18, he prescribed a progression: go privately, take witnesses, tell it to the church. What he didn't say, but the text assumes, is what happens when each prior step fails. The progression isn't optional—it's sequential, and each stage requires the previous one to prove inadequate before the next becomes permissible. Publishing these journals completes that arc.

The 2010 return to Rutbah happened because journalist Greg Barrett explicitly sought a veteran's voice for the story he'd been assigned. Shane Claiborne and others were returning to the Iraqi town where doctors had saved their lives during the 2003 invasion, and Barrett recognized that narrative required military perspective. I was invited specifically because my presence—as someone who had brought violence to Iraq and was now seeking to make amends—was seen as essential to the fuller truth.

What Barrett eventually published in 2012 told a different story. The book that emerged marginalized my experience in ways that distorted both what happened in Rutbah and what the trip revealed about American "peacemaking." The influencer-economic apparatus had already decided which version would be preserved, which voices would be centered, which inconvenient truths could be managed away.

Christ is a public proclamation of the Hebrew God; YHWH is the only one willing to stand in the public square and openly mock the private gods of Entitlement Religion. This isn't a controversial claim, it's basic Second Temple theology. The Law was enshrined, and the Prophets proclaimed, through courageous speech acts rather than commercialized aura farming. Living truthfully is, in itself, a righteous action. Working against the Truth, to conceal your baḏ (alienating) behavior, is to corrupt the image of YHWH in yourself, and also in your followers. That's why James 3:1 is like 'Don't everyone rush to be an educator, lest you be held to a higher standard...

When believers say "the truth will set you free," we're not trafficking in abstractions—we're claiming that disclosure, publication, making-known-in-the-assembly is how righteousness operates in the slow march of history. Obviously, this creates a bit of tension with industrial Christianity's instinct to protect reputation through privacy.

The visible church learned from the empire how to manage information, how to decide what gets remembered and what gets quietly and conveniently "forgotten." The Bible itself testifies against the assumption that history is written only by the victors. The Hebrew Law and Prophets earned the attention of an ancient working class, "the Help," the lowly grunt-workers. And to whom do you think the too-cool-for-school crowd delegated the work of preservation...?

The Bible itself is full of what I'm calling "paleonymic traces;" marginalized figures and suppressed traditions that dominant narratives can never fully erase: judicious confederation before centralized monarchy; Nazarite vows despite Levitical priesthood; prophetic utterance to submit to our enemies; a son of Aaron turning over Jerusalem's ministerial industrial complex.

These stories survive precisely because making known the True and the Beautiful matters infinitely more than protecting institutional dignity.

My journals from Rutbah are primary sources. They're not perfect—I was processing real trauma in real time, navigating complex group dynamics, trying to understand what reconciliation might look like when 👏 you've 👏 been 👏 part 👏 of the violence. But they're contemporaneous, unedited for publication, written without anticipating how the dominant narrative would eventually frame these events. They document what I saw, what I experienced, what I wrestled with. Like me, they simply exist (regardless of who controls the published account).

Some will read these journals looking for ammunition—adversarial fanboys wanting to find dirt, people seeking evidence to invalidate what I say because they don't like how they feel. That's fine. The Christian God is a public God, which means evidence matters, context matters, what actually happened matters more than any individual's reputation, including mine. If someone finds something in these journals that calls my character into question, that's the system working as designed. Truth-telling isn't self-protection; it's opening the accounting ledger so communities can check for themselves.

Others have expressed concern that publishing these journals is vindictive, that it reopens old wounds, that it violates some unspoken Christian obligation to let sleeping dogs lie. But that's empire logic dressed in pious language. Matthew 18 ends with public disclosure precisely because private management failed. The progression isn't circular—you don't go back to private conversation after the church has refused to hear. You make the evidence available and let history do its work.

These journals aren't a counter-narrative in the sense of competing interpretation. They're substrate persistence—the archaeological layer that remains when the topsoil gets turned over. Fifteen years later, people can read both Barrett's book (no longer published) and my journals (published non-consensually), can evaluate the claims against the contemporaneous evidence, can ask their own questions about whose voices got centered and whose were left to languish. That's not score-settling. That's how truth works when the God you serve operates publicly, through witnesses and testimony and making things known in the assembly.

The alternative—keeping these journals private to avoid controversy, protecting institutional reputation, bottling up my true feelings—isn't humility. It's compliance with a system that privileges less influential voices while treating human experience as raw value to be processed, shaped, and controlled. I didn't bring American violence to Iraq only to participate in a gentler form of oppression when I got home.

People are hard-wired to be proud of good shit that we make, like the first drawing you give your parents or the last kiss before you send your child off to college. “The Gospel of Rutba” is not good news, it's #NotMyGospel, because it’s not something I can be proud of. I tried to share my feelings in the moment with people I trusted, and their silence was the nicest thing they did. Silence is like an Exacto knife; it’s made for somewhere between dark streets and surgery, but it’ll do for either in a pinch. Our job is to use what we have wisely, even if you don't get to choose the tool.

Read the journals. Draw your own conclusions. That's what (public) elohim require.