GruntGod 2.1.5: Tropes or Troops

When Storytelling Erases Real Soldiers

The Cain chapter in God Is a Grunt (2nd edition) examines how the "All Soldiers Kill" (ASK) stereotype damages military communities by reducing complex human beings to two-dimensional caricatures. While cutting material to keep the book accessible, I realized the distinction between tropes (storytelling shortcuts) and troops (actual human beings) deserves fuller treatment. Here's why conflating the two is dangerous.

What Are Tropes?

In storytelling, a trope is a recurring pattern or device that audiences recognize immediately. The word comes from Greek tropos (τρόπος, G5158), meaning "a turn or pivot." Tropes turn our attention away from complexity toward simplicity, from reality toward embellishment.

Character tropes are figures whose main purpose is supporting the protagonist or advancing the plot. They don't need depth because they're not the point. Think of Star Trek's "redshirts"—security personnel who beam down to alien planets and die in the first act to establish that the situation is dangerous. We don't learn their names, their backstories, their motivations. They're narrative furniture: necessary, functional, disposable.

Tropes serve a legitimate purpose in fiction. Stories need shortcuts. A two-hour film can't develop twenty characters, so most will be types: the wise mentor, the comic relief, the tough-but-fair sergeant. Audiences accept this because we understand the genre contract: not everyone on screen is equally important.

The problem starts when tropes migrate from fiction to documentary, from storytelling to reporting, from entertainment to news. When real human beings get treated like narrative devices—cannon fodder, props, mascots—their dignity is sidelined.

Military Tropes Through History

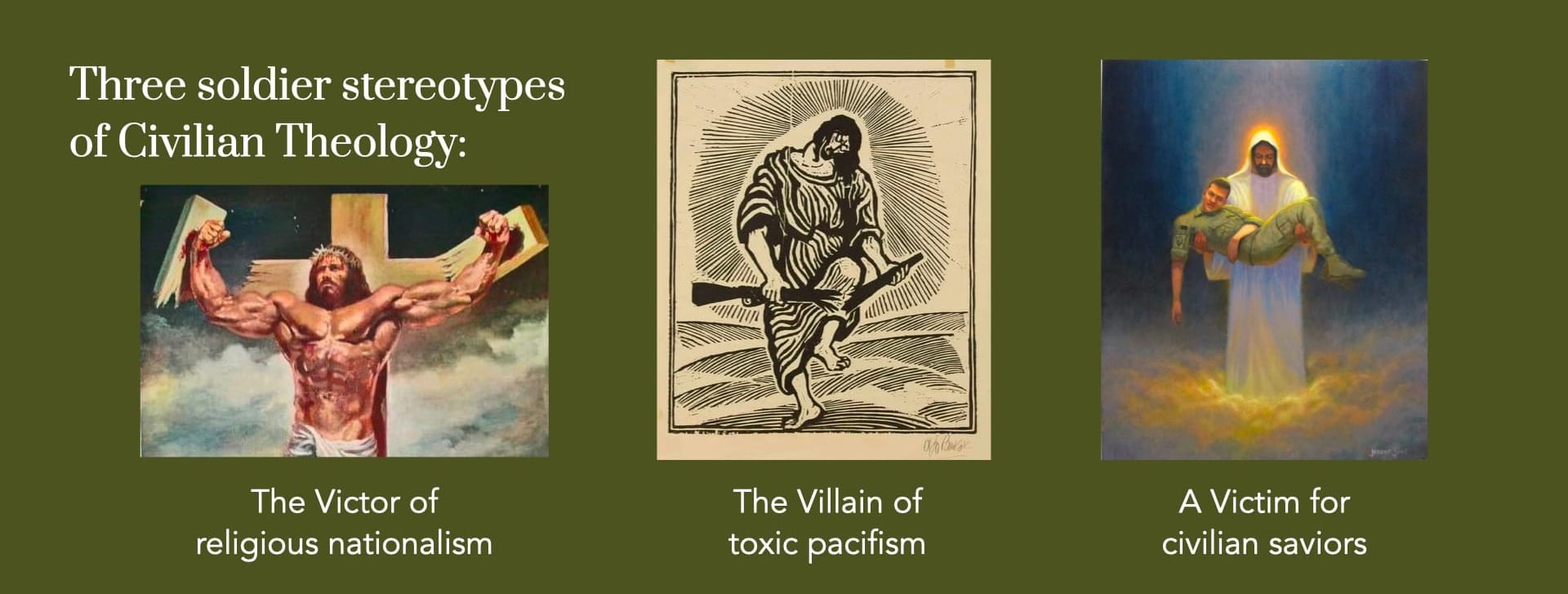

American civilian culture has cycled through three main military tropes, each corresponding to how the civilian gaze wanted to process war guilt.

The Victor (WWII): When the Second World War ended, soldiers came home as heroes. They'd defeated fascism, saved democracy, earned the gratitude of a nation. This trope let civilians celebrate without examining the complex reality of combat. Never mind that many veterans struggled with what they'd seen and done. Never mind that strategic bombing killed hundreds of thousands of civilians. The Victor trope required soldiers to be uniformly heroic, and many veterans played along because that's what civilians needed to hear. The Victor trope is designed to inspire Civilian Pride.

The Villain (Vietnam): A generation later, the script flipped. Vietnam veterans came home to hostility, blamed for an unjust war. Baby-killers. Drug addicts. Morally compromised. Never mind that most were drafted against their will. The atrocity-committing few take center stage while the dutiful ordinands are marginalized. The Villain trope let civilians displace their own guilt onto returning soldiers: We didn't lose the war; they did. We didn't commit atrocities; they did. The Villain trope is designed for Civilian Panic.

The Victim (GWOT): Collective guilt over mistreating Vietnam veterans produced overcorrection. Now every service member is "thanked" for their service, recognized as a dark knight, and pitied as damaged goods. War-torn. Traumatized. Broken. The Victim trope lets civilians perform gratitude while maintaining emotional distance: We honor your sacrifice from over here; you deal with your trauma over there. The Victim trope is designed to elicit Civilian Pity.

All three tropes protect civilians from complex moral reckoning. Heroes don't need our help—they're fine. Villains don't deserve our help—they're bad. Victims need professional help—here's a psychiatrist.

None of these tropes allow for the possibility that military service involves moral complexity that can't be reduced to hero, villain, or victim.

The Christianity Today Case Study

In 2015, I was contacted by Christianity Today to be photographed for an article on moral injury. The design director explained they wanted to "show the toll of war" and have my "face speak to the pain of PTSD." They asked me to wear my old uniform to "potentially allude to the darkness of the disorder."

I had reservations but agreed because the article was ostensibly about how veterans had shaped an academic adviser's thinking on moral injury. Early drafts emphasized veterans as agents—we helped him understand trauma and resilience.

Then the magazine came out with my face on the cover under broken capital letters: "WAR TORN: How a Psychiatrist—and the Church—Are Deploying Hope to Soul Scarred Veterans." 🤦

The article wasn't about veterans helping academics. It was about civilians rescuing damaged veterans. We'd been reduced to tropes—broken props validating the ✌️real✌️ heroes (psychiatrist, church) who were deploying hope to save us.

When I and other veterans pushed back, one wrote:

CT's headline and cover treatment casts veterans as helpless victims... I refuse to be categorized as the world wishes to see me.

But we were already categorized. The magazines had gone to millions of Christian homes, colleges, and bookstores. The trope was cast.

What's Lost When Troops Become Tropes

First: Moral agency. Tropes don't make choices—they exist to be acted upon. The Victor is acted upon by patriotic duty. The Villain is acted upon by the corrupting influence of war. The Victim is acted upon by trauma. None of these narratives allows for the possibility that service members are active moral agents making complex decisions in impossible situations.

Second: Diversity of experience. The "All Soldiers Kill" stereotype assumes every service member has the same experience. But according to 2010 data, 77% of US military personnel are in support roles, not combat arms. Three mechanics for every infantryman. Three finance clerks for every artilleryman. When civilians ask "Did you kill anyone?", they're revealing their assumption that military service reduces to its most dramatic element.

A battle buddy of mine spent his career in the Air Force and constantly apologizes for his experience "not counting" compared to my one Army combat deployment. He's internalized the trope: if you didn't kick in doors, you didn't really serve. This is nonsense—but it's nonsense produced by storytelling conventions that emphasize combat over logistics, violence over service.

Third: Human dignity. This is the deepest loss. When someone becomes a trope, they stop being a person. Star Trek's redshirts don't have dignity because they're not real—they're narrative devices. But when Christians put real veterans on magazine covers as props for civilian hero stories, when civilians perform gratitude rituals that benefit themselves more than veterans, when society reduces complex human beings to victim-mascots—that's a dignity violation.

Genesis 1 says humans are created b'tselem Elohim—in God's image. Whatever else that means, it means humans have inherent worth that can't be reduced to their function in someone else's story. Cain remains b'tselem Elohim even after murdering Abel. Combat veterans remain b'tselem Elohim even after killing in combat. Nobody becomes a prop.

Counterstories as Resistance

Philosopher Hilde Lindemann Nelson argues that oppressed groups can resist harmful narratives through "counterstories"—narratives that complicate simplistic categories and restore moral agency to those who've been reduced to types.

God Is a Grunt attempts this through hagiography: teaching virtue by telling biographical stories of military figures (biblical and historical) that resist civilian tropes. Cain isn't just a murderer—he's the prototype for confession. Moses isn't just a liberator—he's a grunt who never wanted the job. Joshua isn't just a conqueror—he's a priest as much as a warrior.

These counterstories don't erase the difficult parts (Cain did murder Abel; Joshua did lead a violent conquest). They complicate the easy narratives and restore these figures as complex moral agents rather than one-dimensional types.

The same approach works for contemporary veterans. If you've met one vet, you've met one vet. Each has a particular story that can't be flattened into Victor, Villain, or Victim. The church's job—and civilians' job generally—is to listen to particular stories rather than imposing preferred tropes.

That means asking "How was your deployment?" instead of "Did you kill anyone?" It means recognizing that "thank you for your service" might serve your needs more than theirs. It means accepting that some veterans are fine, some are struggling, some are angry, some are ambivalent, and none of them exist to make you feel better about the wars your taxes funded.

Troops aren't tropes. They're people. Treat them accordingly.

This post draws from material cut during revision of the Cain chapter in "God Is a Grunt" (2nd edition), which uses hagiographic methodology to teach virtue ethics through biographical narratives of biblical and historical military figures.