GruntGod 2.3.2: Lost in Translation

How English Bibles Militarize the Militia Dei

This post draws on exegetical material from my revised chapter on Joshua for the second edition of God Is a Grunt.

Every time your Bible says "army" in the Old Testament, you're reading a cultural assumption, not just a translation.

That might sound like academic nitpicking. But translation choices shape how we read Scripture, and how we read Scripture shapes how we think about violence, war, and military service. When English translations consistently render Hebrew terms in ways that emphasize fighting over organization, they're making theological claims whether they intend to or not.

Let me show you what I mean.

The Case of Ṣāḇā

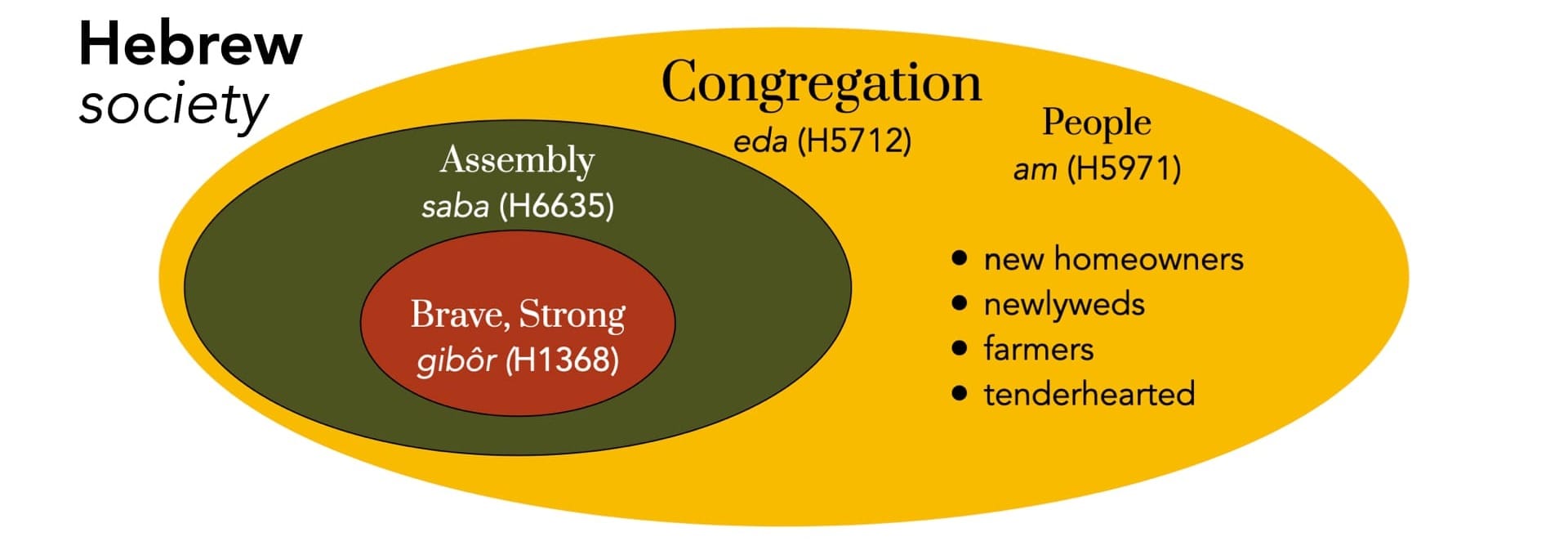

The Hebrew word ṣāḇā (H6635) appears throughout the Old Testament, particularly in Genesis through Joshua. Your English Bible probably translates it as "army," "host," or "fighting force." These aren't wrong exactly, but they're incomplete in ways that matter.

Ṣāḇā's essential element is not being heavily armed or highly trained. It's being carefully organized. The word emphasizes assembly, arrangement, coordination—the same qualities we associate with civilians standing in formation or workers organized into shifts. Fighting might happen, but it's not definitional.

Consider the first use of ṣāḇā in Scripture. Genesis 2:1 says "Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their [ṣāḇā]." The NRSV translates this as "multitude." The ESV goes with "host." The NIV says "array." None say "army," because that would be absurd. The heavens and earth aren't preparing for combat. They're organized, arranged, assembled according to God's creative ordering.

The second use? Exodus 6:26, referring to Hebrew slaves while they're still in bondage in Egypt. The NRSV translates ṣāḇā here as "companies." Again, not "army"—because enslaved people aren't a military force. They're organized in work groups, arranged by family units, assembled by tribe.

But by the time we get to Numbers and Joshua, English translations shift toward martial language. Suddenly ṣāḇā becomes "army" or "host" in ways that emphasize military might rather than organizational precision.

Americans and Pedestals

Here's where cultural assumptions become unavoidable. Americans put their military on pedestals. We think of soldiers first as warriors and only secondarily as citizens organized for public service. That cultural assumption shapes how translators render ṣāḇā—and how readers understand it.

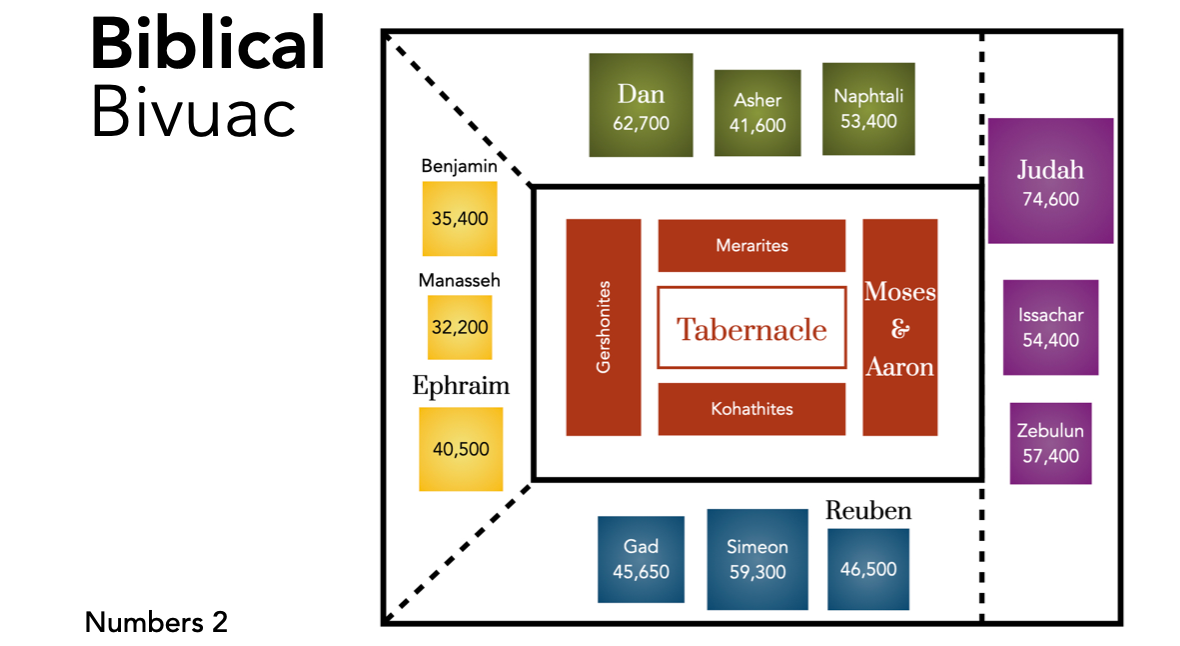

Look at Numbers 1:3. The Hebrew says God tells Moses to count all men "from twenty years old and upward, everyone in Israel able to [ṣāḇā]. You and Aaron shall enroll them, [ṣāḇā]."

Most English translations render this something like: "everyone in Israel able to go to war...enroll them, company by company" (emphasis added). The word "war" appears in the English but not in the Hebrew. The translators have interpreted ṣāḇā through a martial lens that the text itself doesn't require.

A more literal rendering would be: "Let those who are able to be assembled be assembled." This catches the organizational emphasis while leaving the purpose more open. Yes, one reason for assembly is defense against enemies. But a much more pressing concern for Israel at this moment is getting organized to receive their portion of the Promised Land.

In fact, the majority of the book of Joshua focuses on methodical distribution of land to tribes according to their size. Battle is not the main story. It's a prelude to the real mission: fair allocation of resources and maintenance of just order.

What Changes When Translation Changes

What happens when you read Joshua thinking of ṣāḇā as "assembly" rather than "army"?

First, the emphasis shifts from military prowess to civic organization. Israel's success depends not on superior weapons or battlefield tactics but on everyone doing their assigned part within a coordinated system. When Joshua warns the people to "keep [šāmar] yourselves from the things devoted to destruction, lest they make the camp [maḥănê] of Israel a thing for destruction" (Josh. 6:18 ESV), he's emphasizing collective accountability, not individual combat effectiveness.

Second, the categories of "soldier" and "civilian" become harder to distinguish. The Hebrew word maḥănê can be translated as "camp," "host," "company," or "army." It refers to all of Israel, not just those who fight. Everyone is liable to serve in some capacity, from priests to musicians. The Jericho conquest involves a parade formation with priests carrying the ark, musicians blowing trumpets, and fighting men bringing up the rear. Who's the "army" here? Everyone. The whole assembly.

Third, the consequences of individual failure become clearer. After Jericho, Israel suffers a debilitating loss at Ai because one soldier—Achan—violated the rules of engagement by looting. When his theft is discovered, Achan is stoned and his family burned alive. The text doesn't flinch from the brutality, and neither should we. But notice the logic: Achan's individual corruption makes the whole maḥănê liable for destruction. His failure isn't just his problem. It pollutes the entire assembly, soldier and civilian alike.

This is not how we think about military failure in America. We compartmentalize: "That's one bad apple." "You can't blame the whole unit." "Keep it in perspective." But the Hebrew text won't let us compartmentalize. The ṣāḇā—the assembly—succeeds or fails together.

Translation as Theology

Translation is always interpretation. When English Bibles consistently render ṣāḇā in ways that emphasize martial elements, they're making interpretive choices that reflect modern assumptions about what militaries are for.

Those assumptions aren't neutral. They shape how American Christians think about military service, how we justify violence, how we distinguish "warriors" from "civilians," how we handle institutional corruption.

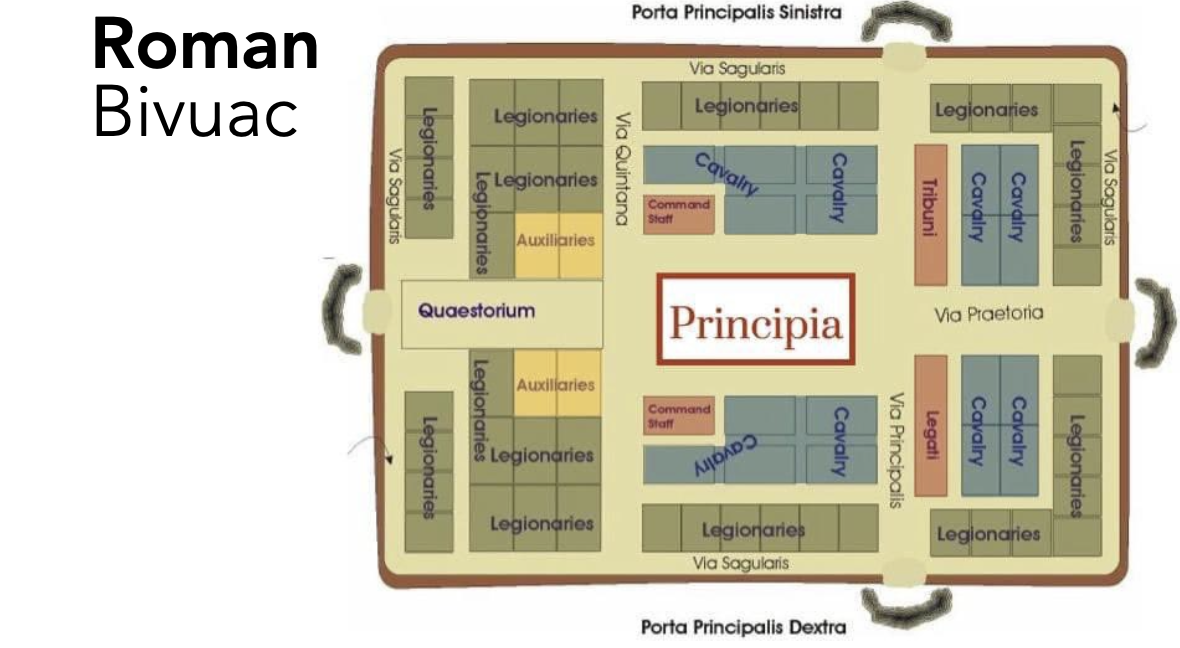

What if we translated more literally? What if we let the organizational emphasis come through? We might start seeing that ancient Israel's "military" looks less like the modern US Army and more like an entire community organized for maintaining just order—with fighting as a necessary but subsidiary function.

We might start asking whether the line between soldiers and other public servants is thicker than it should be. We might start recognizing that when one cop brutalizes someone in custody or one soldier violates ROE, the moral pollution affects the whole community, not just the individual or their immediate unit.

We might start reading Joshua not as a manual for holy war but as a warning about what happens when servant-protectors lose sight of their primary mission: maintaining the order God established, from the bottom up.

That's not in the Hebrew text because I'm reading into it. It's in the Hebrew text, and our translations have been reading around it.

Next time your Bible says "army," remember: you're reading a choice, not just a word. Ask what the translators emphasized—and what they obscured.

Logan M. Isaac served as an artillery forward observer in Iraq and the second edition of God Is a Grunt uses hagiographic methodology to teach virtue ethics through military biography. Subscribe for more content wrestling with military ethics and biblical theology.