GruntGod 2.3.1: Etymology as Ethics

Why the Origin of 'Military' Matters

This post draws on exegetical material from my revised chapter on Joshua for the second edition of God Is a Grunt.

What if I told you the US Army's primary mission isn't fighting wars?

You'd probably think I'm splitting hairs or playing word games. But according to 10 USC § 7062, the statutory language establishing the Army's purpose lists three capabilities that precede "overcoming any nations responsible for aggressive acts":

- Preserving the peace and security [of the United States]

- Supporting the national policies

- Implementing the national objectives

Fighting comes fourth. Dead last.

This isn't bureaucratic accident. It reflects something ancient and essential about what militaries were designed to do—something we've largely forgotten. The etymology tells the story.

From Miles to Militia

In Latin, militia (military force) derives from miles (soldier). The origin of miles is disputed, but many scholars trace it to mille—one thousand. The same root that survives in our metric prefix milli-.

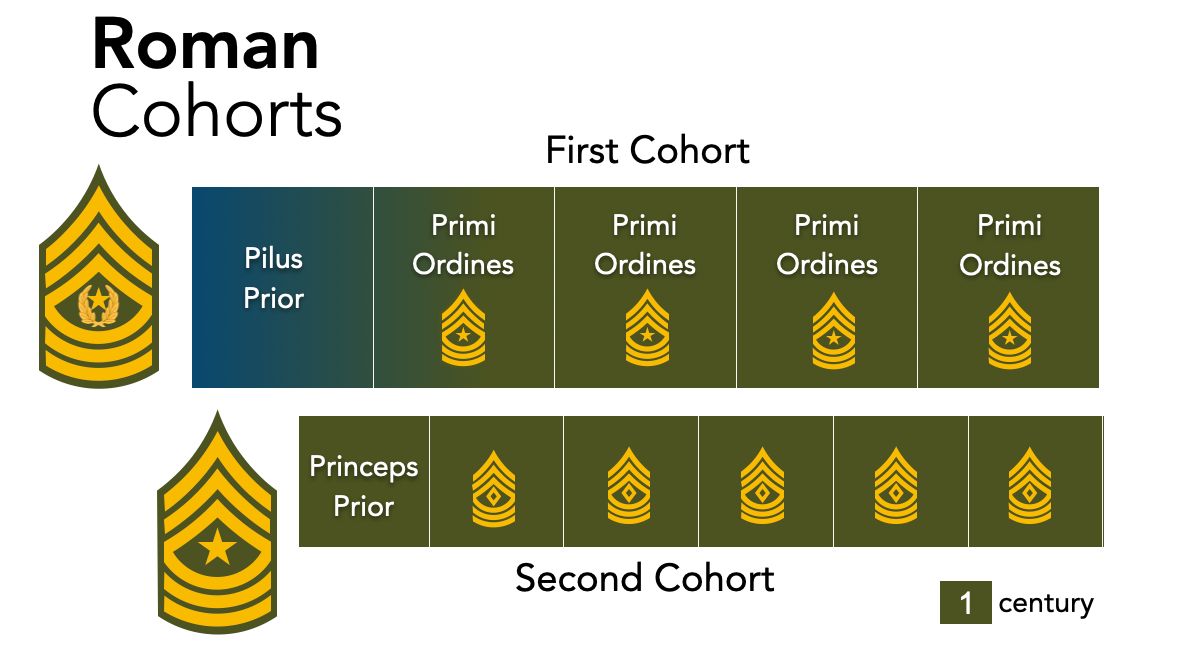

Why would "soldier" come from "thousand"? Because the essential characteristic of early militaries wasn't weaponry or combat prowess. It was organization. The ability to assemble people, to count them, to deploy them in coordinated formations. A mille—one thousand—represented a unit of human organization, not a body count.

This matters because militia originally referred to ad hoc local forces organic to a community rather than professional armies loyal to distant kings. Militias existed to maintain order within communities. They weren't designed primarily for external conquest but for internal stability. Any battles that might erupt were meant to serve that organizing purpose. Fighting was never supposed to be soldiers' primary function.

The Greek equivalent reveals the same priority. Stratiotes (soldier) comes from stratos, meaning "arrangement or layered"—the same root that gives us "stratosphere." Epic poetry used stratos to describe commoners who could be called upon to serve. Not because they were warriors, but because they could be arranged, organized into functional units.

What We've Corrupted

Somewhere along the way, we flipped the script. We started thinking of militaries primarily as fighting forces, with peacekeeping and order-maintenance as secondary missions we grudgingly accept. The linguistic evidence suggests this gets it exactly backward.

Before America had a unified military, it had many state militias—groups of citizens willing to fight beside one another to oppose King George and other threats to our fledgling democracy. A few of today's 54 National Guard units trace their history to these militias. But as our nation grew up, it absorbed and organized them into a single modular force designed more for projecting power abroad than maintaining order at home.

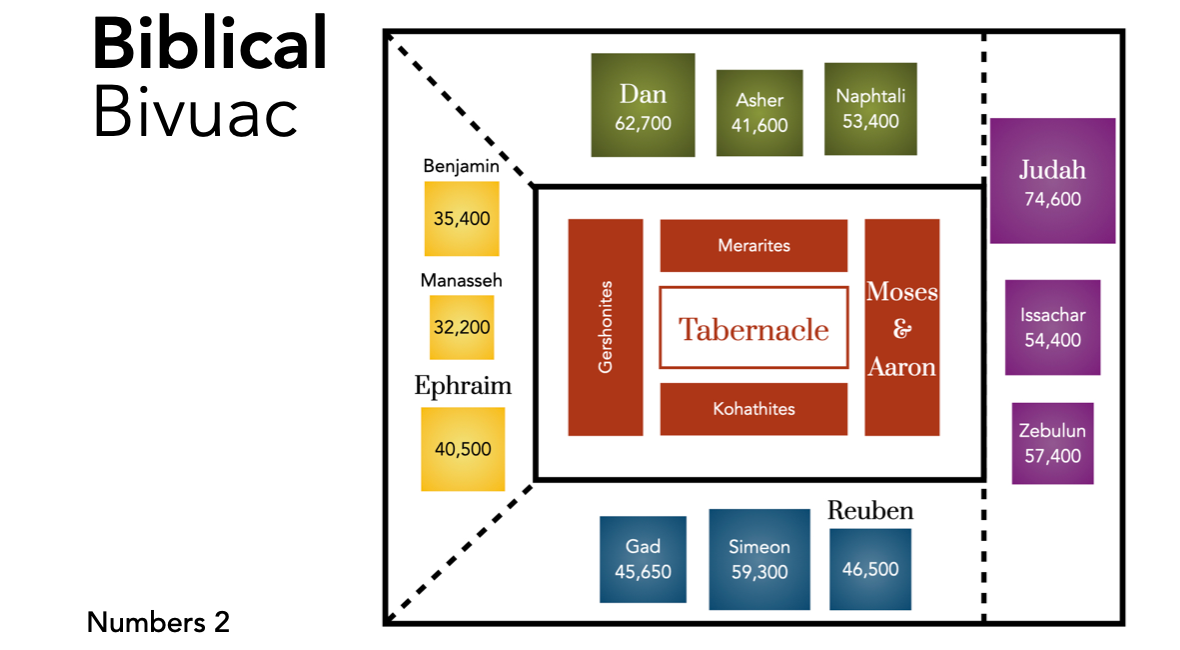

The book of Joshua shows this process in reverse: Israel conquers the Promised Land as a cohesive unit under a strong leader before devolving into tribal forces competing for power and resources. And here's what's crucial: less than a quarter of Joshua describes expelling Canaanite inhabitants with violent force. Ten chapters—13 through 22—outline in painstaking detail how the land will be allocated to the tribes according to their size. Battle is not the main story. It's merely a prelude to the real mission: fair distribution of resources and maintenance of social order.

The Biblical Pattern

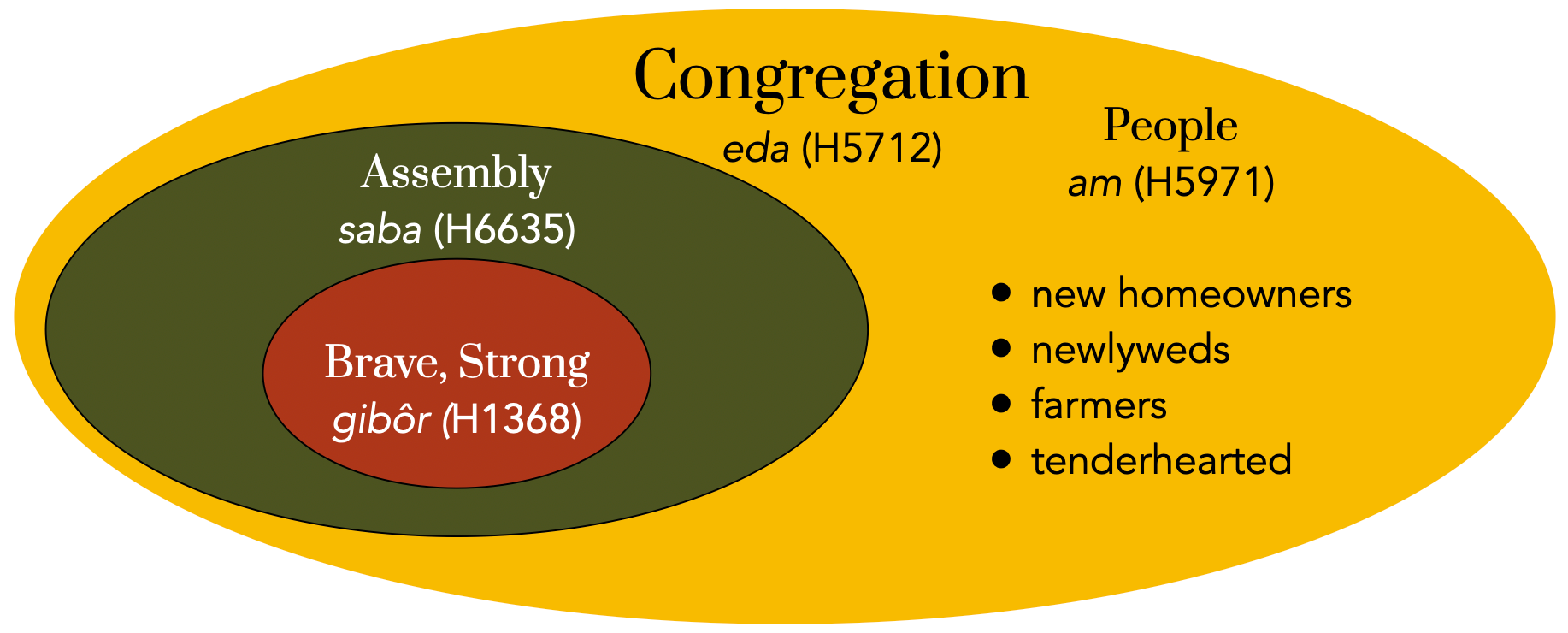

When you read about "armies" or "hosts" from Genesis to Joshua, the Hebrew word is ṣāḇā (H6635). Its essential element is not being heavily armed or highly trained, but being carefully organized.

The first ṣāḇā in Scripture? The heavens and earth (Gen. 2:1). The second? Hebrew slaves while they're still in bondage in Egypt (Exod. 6:26). Neither group is preparing for battle. Both are being counted, organized, assembled.

When God tells Moses to take a census in Numbers 1:3, English translations usually render it as "everyone in Israel able to go to war...enroll them, company by company." But the Hebrew is simpler and more fundamental: "Let those who are able to be assembled be assembled." One reason for assembly is defense against an enemy. But a much more pressing concern for Israel is getting a piece of that promised land.

Americans really put their military on pedestals, which skews how we read these texts. We assume "army" means "fighting force." But the Hebrew consistently emphasizes organization, precision, and accountability—not firepower.

Why This Matters Now

Recovering the original meaning of "military" could reshape how we think about service. If militaries exist primarily to maintain just order within communities—not to project violence outward—then the line between soldiers and other public servants becomes much thinner.

Fire protection. Law enforcement. Emergency services. These aren't auxiliary functions that "also" serve the community. They're the primary expression of what military service was supposed to be. Combat arms? That's the backup plan for when order breaks down and violence becomes necessary.

This isn't wishful thinking or pacifist revisionism. It's what the etymology reveals and what the biblical texts consistently emphasize. When Joshua warns his troops to "keep yourselves from the things devoted to destruction, lest you make the camp of Israel a thing for destruction" (Josh. 6:18 ESV), he's not worried about tactical errors. He's worried about moral corruption. The rules of engagement don't just protect noncombatants—they protect the protectors themselves from becoming the kind of people who violate the order they're supposed to maintain.

One soldier's theft corrupts the whole unit. One cop's brutality betrays the whole force. That's not modern sensitivity or political correctness. That's the ancient logic embedded in the etymology itself.

Miles comes from mille. Soldiers exist to be called, organized, and deployed in service of just order. When we forget that and start thinking of them primarily as killers, we corrupt both the institution and the individuals within it.

The US Army got it right, even if we've forgotten why. Fighting comes last. Maintaining order comes first.

That's what it means to be miles. That's what it means to serve in the militia Dei.

Logan M. Isaac served as an artillery forward observer in Iraq and trained in virtue ethics under Stanley Hauerwas at Duke. His second edition of God Is a Grunt uses hagiographic methodology to teach virtue ethics through military biography. Subscribe for more content wrestling with military ethics and biblical theology.