GruntGod 2.1.3: Reading Genesis 4 in Hebrew

What We Miss About Cain

The Cain chapter in God Is a Grunt (2nd edition) argues that Cain is the Bible's prototype for confession and reconciliation after moral pain—good news for combat veterans who feel defined by their worst actions. But to keep the book accessible to military families, I cut most of the Hebrew exegesis. For readers who want the linguistic apparatus, here's what English translations miss about Genesis 4.

"What Have You Done?" (Gen. 4:10)

When God confronts Adam and Eve after they eat the forbidden fruit, God asks them separately: "Where are you?" (3:9) and "What is this that you have done?" (3:13). The Hebrew emphasizes the distance between person and deed—this thing you have done, not this thing you have become.

By the time God confronts Cain, the question has changed. God asks simply, "What have you done?" (מֶה־זֹּ֣את עָשִׂ֑יתָ, meh-zot asita, 4:10). The demonstrative zot (this) is still there, but the question is more direct. God can now recognize sin without confusion.

This is the Question of Killing—asking not just about mechanics (how), but about meaning and purpose (why and when). It's the question combat veterans need asked but rarely get. Instead, civilians ask the ASK question: "Did you kill anyone?" A voyeuristic yes/no that treats killing as the defining feature of military service.

Genesis models a better approach: What have you done? Not what have you become, not are you a killer, but what happened and why?

"My Punishment Is Too Great" (Gen. 4:13)

Cain's response is typically translated: "My punishment is greater than I can bear" (NRSV, ESV, NIV). But the Hebrew is more ambiguous.

Gadol avoni mineso (גָּד֥וֹל עֲוֺנִ֖י מִנְּשֹֽׂא) could mean either "my punishment is too great to bear" or "my iniquity is too great to be forgiven." The word avon (עָוֺן, H5771) is the key: it means "iniquity, guilt, punishment" depending on context. It's the same word used in Leviticus 16:21 when the high priest confesses "all the iniquities [avon] of the people" over the scapegoat on Yom Kippur.

Cain is making the first recorded confession of guilt in scripture. He's not complaining about punishment being too harsh—he's expressing the crushing weight of moral pain. "What I've done is enormous. The guilt is unbearable."

This is a huge improvement over his parents. The man blamed Eve. Eve blamed the snake. Neither acknowledged their own agency. Cain admits: I did this. It's heavy. I can't carry it alone, please don't make me!

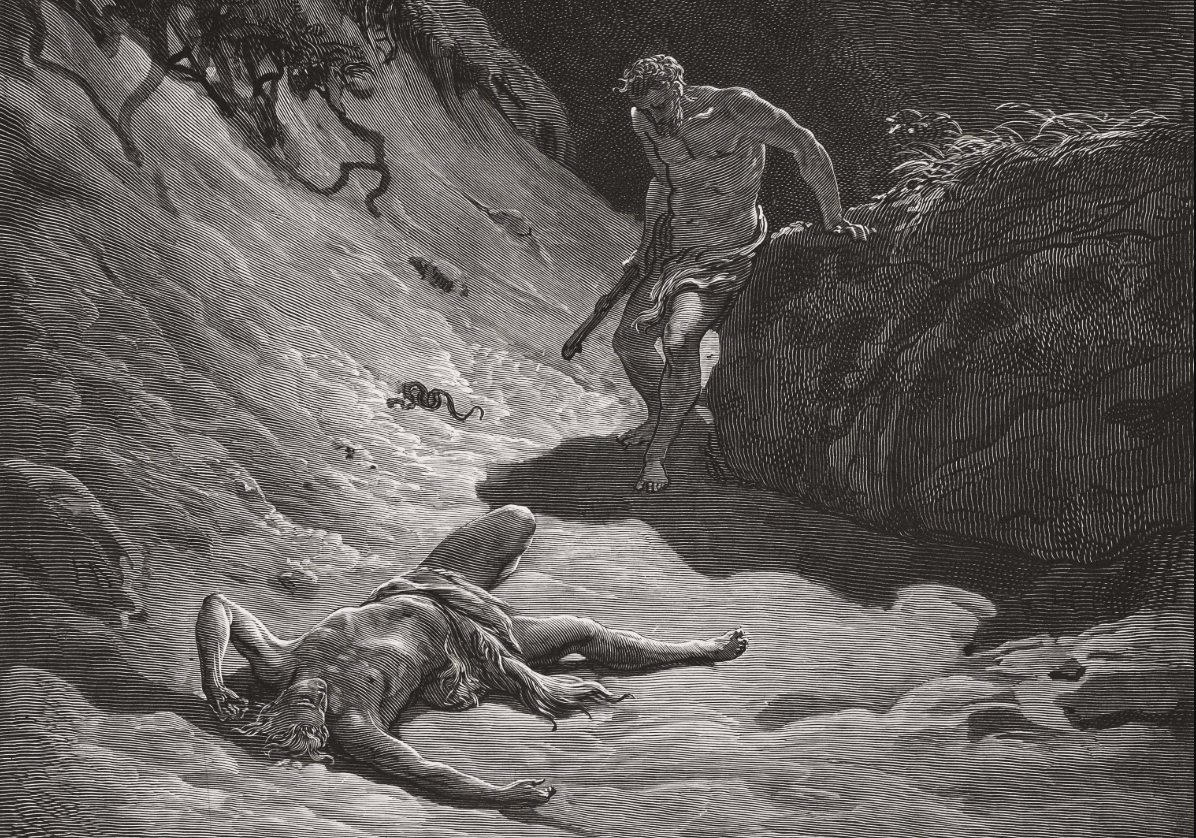

"A Fugitive and a Wanderer" (Gen. 4:12, 14)

English translations have God telling Cain he will "be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth" (NRSV). But the Septuagint (Greek translation, ~250 BCE) reads: stenōn kai tremōn esē (στένων καὶ τρέμων ἔσῃ)—"you will be groaning and trembling."

Stenōn (στένων) comes from stenos (στενός, G4728), meaning "narrow, tight, constricted." A derivative word, steni, means "prison." It evokes the feeling of being trapped, enclosed, unable to breathe.

Tremōn (τρέμων) comes from tremō (τρέμω, G5141), meaning "to tremble with fear or dread." It's used in Mark 5:33 for the hemorrhaging woman who approaches Jesus "in fear and trembling."

Put them together: Cain will experience anxiety (trembling) and avoidance (constriction). He'll feel trapped, unsafe, constantly on edge. This is textbook post-traumatic stress.

God isn't pronouncing a supernatural curse. God is explaining the natural psychological consequences of violence: it makes you feel isolated, unsafe, and unable to trust. The wound isn't from God—it's from the ground that had to absorb Abel's blood.

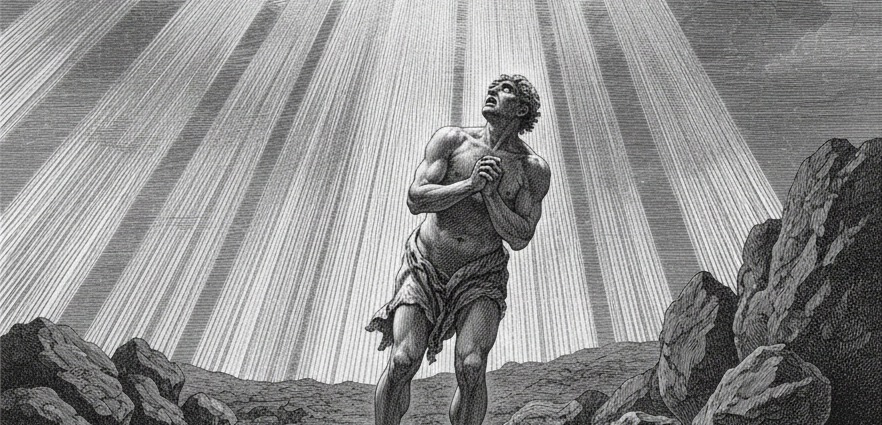

The Mark as Protection (Gen. 4:15)

God says: "Whoever kills Cain will suffer a sevenfold vengeance." Then God puts a mark (ot, אוֹת, H226) on Cain.

The word ot is the same one used in Genesis 1:14 for the lights in the sky that serve as "signs" (otot, plural) to mark seasons, days, and years. These aren't arbitrary—they're functional markers that help orient humanity in time and space.

Cain's mark serves the same purpose: it orients humanity morally. Just as stars mark time, Cain marks the transition from shame to guilt, from hiding to confession.

The mark isn't primarily for Cain—it's for everyone else. It's God's way of saying to humanity: "This person has done something terrible and confessed it. Do not treat him as expendable. Do not confuse his actions with his being. He remains under my protection."

This is the opposite of Basil of Caesarea's fourth-century interpretation, which claimed the mark was "a conspicuous sign...proclaimed to all that [Cain] was the contriver of unholy deeds." Basil thought the mark broadcast Cain's sin as a warning.

But Genesis never says the mark identifies what Cain did. It protects him from what others might do to him based on their assumptions about what he's become.

The Mark as Type (Gen. 4:15)

The Septuagint uses sēmeion (σημεῖον, G4592) to translate the Hebrew word ot, but typos (τύπος, G5179), also means "mark, impression, pattern, example." Different words, very similar effect in modern thought (thanks to the interesting etymology of the English word stereotype).

A typos can mean:

- A mark left by a blow (like a bruise or brand)

- A mold or pattern for making copies

- An example or prototype to follow

Cain is a typos in all three senses:

- He bears a literal mark from God

- He establishes a pattern for others to follow

- He becomes an example—not of unrepentant murder, but of post-trauma confession

Paul uses typos this way in Philippians 3:17: "Join in imitating me, and observe those who live according to the example [typos] you have in us." Cain is the Bible's prototype for what to do after you've done the worst thing: acknowledge it, accept the consequences, trust God's protection, and keep living.

Why This Matters

Most English readers come away from Genesis 4 thinking Cain is cursed, cast out, marked as a murderer. They see him as the Bible's first villain—maybe even "from the evil one" (1 John 3:12).

The text itself tells a different story. Cain experiences natural consequences (trauma, isolation, agricultural difficulty), confesses honestly, receives divine protection, and gets to keep living. He's not a cautionary tale about damnation—he's an example of how to move through guilt without being destroyed by shame.

For combat veterans who feel defined by their worst actions, Cain offers a roadmap: Name what you've done. Feel the weight of it. Don't hide from God or from community. Trust that your humanity remains intact even when it's obscured. Accept that trauma is part of the cost, but not the end of the story.

Genesis 4 isn't about a murderer. It's about the first person to demonstrate that confession is possible after moral injury—and that God's protection extends even (especially) to those who think they've gone too far.

This post expands Hebrew and Greek exegesis cut from the Cain chapter of "God Is a Grunt" (2nd edition), which uses hagiographic methodology to teach virtue ethics through biblical military figures.