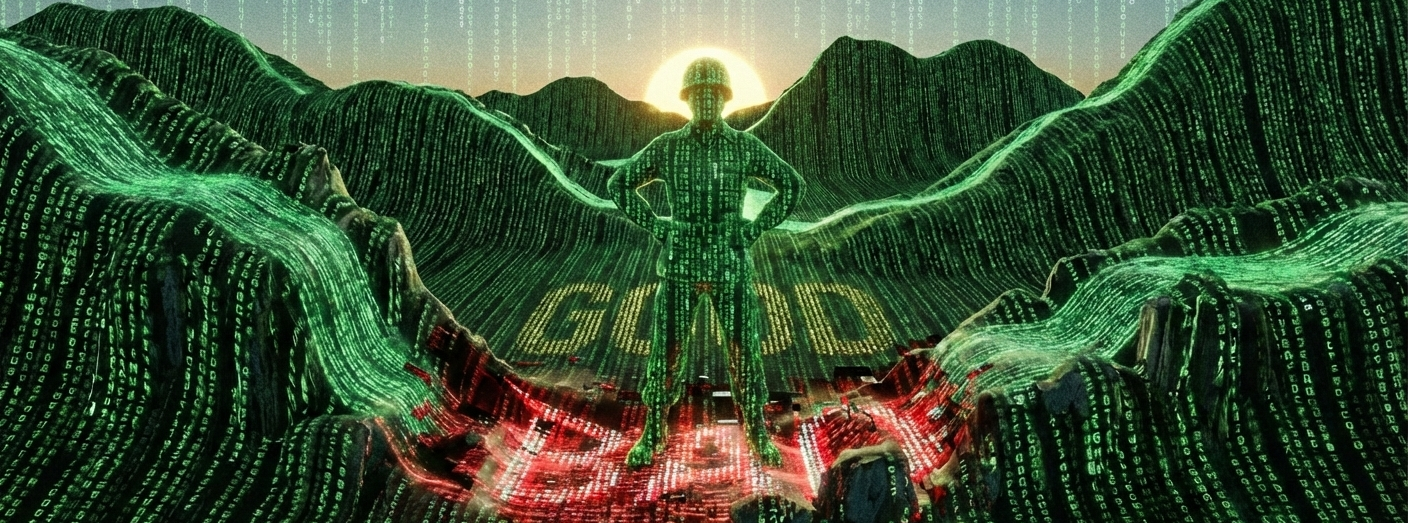

Don't be baḏ: a martial theodicy

Genesis on evil, isolation, and why you are good

Everything in creation is tov (טוֹב, H2896). Light: good. Land: good. Vegetation: good. Sun, moon, stars: good. Animals: good. Humans made in God's image: very good.

Then Genesis 2:18 drops the only "not good" in creation: "It is not ṭôḇ that adam should be baḏ."

The Hebrew word is בַּד (H905), transliterated as bad. It means alone, separated, isolated—cut off from community. It comes from the root bāḏaḏ (בָּדַד, H909), which Isaiah 14:31 uses to describe a military deserter who's abandoned his post and left his unit.

Genesis establishes two things in creation's source code: goodness and togetherness. Everything else flows from there.

Evil Isn't a Thing

We talk about evil like it's a force—something dark, powerful, independent. Genesis says that's wrong. Evil isn't a positive entity. It's the absence of good, the lack of togetherness. Evil is what happens when isolation fractures community.

Think of it like cold. Cold isn't a thing—it's the absence of heat. You can't generate cold, only remove heat. Same with evil. You can't create it, only withdraw from goodness.

This matters because it reframes how we understand “sin” and moral injury. People aren't evil. People do isolating things. There's a difference between what you are and what you've done, between ontology and action.

Genesis is careful about this. When God confronts the (hu)man and Eve after they eat the forbidden fruit, God asks: "What is this that you have done?" (Gen. 3:13). Not "what have you become," but "what is this thing you did." The demonstrative keeps person and deed separate.

How Isolation Works

After they screw up, the first humans do what everyone does: they hide. They isolate from God by ducking into the trees, embarrassed at their nakedness. Then they isolate from each other through blame; the (hu)man blames (wo)man, the woman blames a non-human animal.

This is the pattern. We make things worse by recoiling 🐍 inward with our shame and treating everyone else as the problem.

God seems genuinely confused by human shame. "Where are you?" God asks (Gen. 3:9), like isolation is foreign to divine experience. Which makes sense—if God is fundamentally relational (Trinity and all that), then isolation is the opposite of divine nature.

Bad as Military Metaphor

The Hebrew bad appears throughout scripture with military connotations. A lone soldier cut off from his unit. A deserter who's left his battle buddies. Someone who's broken formation and lost the protection of community.

This is why post-combat stress is so dangerous. When veterans hide from others (because of embarrassment) or hide from themselves (through justification), they're repeating the Genesis 3 mistake. They're going bad in every sense; isolated, separated, cut off. Bad bugs infiltrate their personal inner sanctum, their soul (psychē, G5590)

The threat isn't that they've become something monstrous. The threat is that they're alone with their deeds and have no way to process them. The result is what Hilde Lindemann calls "infiltrated consciousness," and it is a form of internalized oppression.

Why You're Still Good

Human dignity is ontological—it's written into creation's operating system. You inherited goodness from being made in God's image. That can't be uninstalled.

“Sin” is like corrupted files; not the opposite of a file, but the same thing... just fµ¢ked up. It can make the system run poorly, glitchy AF, but it can't fundamentally reprogram what you are. Goodness is deeper than any corrupted file.

Combat veterans often internalize the message that killing or participating in violence has fundamentally changed them—crossed a line, become something other. Genesis says that's bullshit. What you've done may have obscured your goodness, made it harder to see clearly or believe as freely, but it hasn't eliminated it.

If anyone tries to convince you that you're not good, tell them to read their Bible. Better yet, send them here and Grunt Works’ll sort them out.

The Path Forward

The solution to bad (isolation) isn't shame management or moral improvement. It's reconnection; to people and to place. The promise of land is the promise of community.

Cain figures this out after killing Abel. Instead of hiding like his parents, he confesses: "My iniquity is too great to bear" (Gen. 4:13). He admits the weight, doesn't minimize it, doesn't deflect. And God protects him—puts a mark on him that says to everyone else, "This person has done something terrible and confessed it. Do not treat him as expendable."

The mark isn't Cain's sin broadcast to the world. It's God's protection extended to someone who realized too late that he'd gone too far.

What This Means Practically

If evil is isolation and goodness is community, then the church's job isn't to "save" or "fix" broken people. The church's job is to refuse stereotypes that obscure people's fundamental goodness and to challenge isolation by creating communities of honest confession.

That's it. That's the whole gig.

Not moral lectures. Not shame management. Not fixing what's supposedly broken. Just refusing to let people stay bad—alone, separated, isolated—when the source code says everyone needs a battle buddy.

You are good because God made you good. A corrupted file doesn't unmake the operating system. It just makes things glitchy until you reconnect and run the restoration protocol. When bad bugs infect your system, you just need to install the latest update. Whether that is intellectual for you (better theology) or somatic (better community), or both! Both is usually best.

Which is theological jargon for: stop hiding, find your people, tell the truth about what you've done, and trust that your humanity remains intact even when it's obscured.

That's what Genesis says about evil. It's not a force, it's the absence of good. And the absence of good is always, fundamentally, the presence of isolation.

Don't stay bad. Find your battle buddies.